Executive Summary

While most brands actively invest in Customer Retention Strategies, the One-time buyers represent the largest overlooked opportunity for retail commerce marketers today. It has been that way as long as there have been retail sales.

Rather than focusing on the Trial Buyers (one-time purchasers), many organizations remain focused on acquisition as the avenue for growth.

Yet the stark reality is that the majority of those acquisitions lead to just a single purchase with no subsequent value.

Meanwhile, numerous published studies illustrate the cost of acquiring a new customer is at least 5 times the cost of maintaining an existing customer. This results in a significant waste of time, money, and resources that could be focused on cultivating repeat customers.

It’s important to understand that the bid-based digital media market has a near perfect structure to make customer acquisition the marketing problem it is today.

- It has a massive number of participants – ie, “participant saturation”

- It is effectively controlled by a duopoly – Facebook and Google

- The duopoly has raised prices on average 10% per year, doubling costs in just 7 years

- While household income and low inflation has kept retail pricing relatively static

The cost of acquisition has become onerous at best for most retailers. This white paper defines the one-time buyer opportunity in substantial detail. It will help you to weigh the impact one-time buyers have on your business, the opportunities it presents if addressed meaningfully, and help organizations break the “acquisition affliction” that plagues retail commerce.

Background

If you ask most retail and eCommerce businesses what their biggest problem is, they tend to consistently define it as one of the following:

- Customer acquisition

- Revenue growth

- Margin compression [discounting]

If you’re in retail / e-commerce, you may well be thinking “all of the above.”

The current wave of retail transformation (sometimes referred to as the “retailpocalypse”) suggests that many organizations simply aren’t solving these problems despite years of efforts, new websites, management and staff changes, and regularly “refreshing” the brand.

While each of these can have real value and may be necessary steps towards improving struggling direct-to-consumer businesses, our research and experience strongly suggests there is a more fundamental problem.

However, if this problem is addressed in a strategic and methodical manner, it does more than just produce a positive change. In fact, it can quite literally remake the character and profitability of a retail business.

In order to implement a change of such a magnitude, the first thing we have to learn is just what we’ve been missing – and one of the biggest misses of all time in retail commerce has quite consistently been the one-time buyers brands have now, and consistently add.

While it is reasonable to assume that a big miss like this has been solved before, many brands and retailers have described it not as a problem worthy of sustained focus, resources, and effort, but rather “just a part of the business.”

Our work suggests these are more expressions of frustration with one-time buyer problems than facts or some set of natural laws of human behavior.

Some brands deflect this problem by referring to these one-time buyers as “trial buyers” – and declare the mere feat of getting customers into trial as acquisition success. While we would wholeheartedly agree that a net new “trial” buyer is not inherently bad for business, it is often a critical starting point. Our evidence illustrates that questioning the value of trial buyers is a success facilitator that most retail commerce brands simply haven’t adopted to date.

Success is often defined by customer acquisition “count” alone. In some cases, this leads to what we refer to as an “Acquisition Addiction.”

Defining the One-Time Buyer Problem Clearly

Missed opportunities are essentially problems for your business, and the end result is that your cost structure is higher than it should be. So, why are one-time buyers such a big problem? Especially when the goal is to generate revenues and acquire customers now?

These short term goals are of course, the very beginnings of the one-time buyer problem. In reality, it goes much deeper.

“That which gets measured gets done”

Surely, revenue and acquisition are strong objectives that have been easily measurable for many years. In turn, it is not surprising that most retail / ecommerce organizations are doing a fine job at it. Why? Because “that which gets measured gets done.”

Retail has done a good job at measuring revenue for a long time — POS and ERP made that measurable in physical retail decades ago. Meanwhile, acquisition and its costs have become far more measurable on digital channels. The mass migration to efficient digital acquisition has also been enabled through superior measurement of acquisition and its costs.

While attribution is still a challenge, we won’t address it herein. Although it is a serious concern in justifying investments in a customer acquisition, it’s still not nearly as large of a problem as what happens after the customer enters “trial.”

Defining the Magnitude of The One-Time Buyer Problem in Your Company

There are multiple dimensions to how we determine the magnitude of a one-time buyer problem. The first and simplest is to just count the number of unduplicated individuals with only one transaction on their record.

It is worth noting once more how important it is to get a clean count by having a reliable mechanism to roll up the correct transactions under an individual buyer. Underestimating the complexity of the “roll up” and de-duplication process will add substantial noise to your data, and high fidelity is required to get a consistently effective solution to the one-time buyer problem (and other problems like it).

With that file in hand, we segment out the group of buyers with a single transaction. This is what is referred to as “the universe” of all one-time buyers.

The vast majority of retail / ecommerce organizations have a very large percentage of one-time buyers. For ecommerce-only businesses, the number tends to be a bit lower, but has still been steadily rising industry wide between 51-79%.

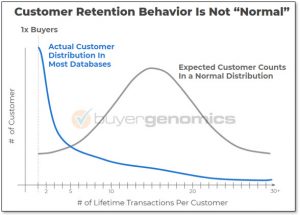

The values for the percentage of one-time buyers across all retail commerce organizations is not a normal distribution (the familiar “bell curve”). Instead, buyers stack up substantially around one purchase.

Is Your One-Time Buyer Problem Even a Problem Worth Solving?

For most retail / ecommerce organizations, a look at the percentage of buyers in their respective customer databases is usually sobering. However, the benefit is that it becomes quickly clear that this is a large enough problem to warrant focus and investment in solving.

There is good news and bad news in this top-level dimension of the problem. While large, these buyers are not homogenous (the same), they are typically quite heterogeneous (different) from one another. In many cases, the only thing your one-time buyers have in common is they are all in the trial stage of their relationship with your business and your brand. The longer trial buyers stay in the “trial” stage, the less likely they are to become profitable, and loyal customers.

Further segmenting your customers will allow you to tailor different types of communications to different types of individuals. Depending on the size of your customer database or file, we would segment it accordingly.

We will further segment this population in a later step. Your total universe likely contains a percentage of customers that are long gone and are overlapping with the “Inactive” segment. Therefore, they are not worth a substantial investment in time and money to pursue. These individuals may not have the value of a more recent one-time buyer, but they do serve to illustrate the value lost because they were not focused on earlier in their Buyer Lifecycle.

Defining The Dimensions of Your One-Time Buyer Problem

When solving any problem, the key is to break it down into its component parts, and solve it one piece at a time.

Predict the Timing of Your Second Purchase

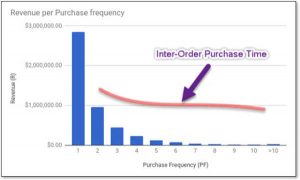

First, we’ll want to know the median number of days between the 1st and 2nd purchases across all customers that have bought at least twice. This is known as the inter-order purchase time (we’ll refer to it as their “IPT”). It is a simple but effective way to start identifying the length of time (measured in days) before a typical repeat customer makes their second purchase. If a customer goes beyond the median number of days for a second purchase, it is a milestone for action.

What If We Miss an Expected Second Purchase?

Now that we have derived a good purchase window for the second sale, we’ll want to determine which buyers look more like they’ve missed that window.

In order to answer that question, you need to calculate the days since the first purchase for all one-time buyers.

Those who made their first purchase relatively recently are more likely to make a second purchase. Compare this to the population we just calculated (your IPT) and we’ll know how close or far we are from the norm for the second purchase.

Mean Reversion Can Serve You

This is effective, as data scientists have consistently found over time and across large datasets a powerful force known as “mean reversion.”

Mean reversion says – with all other factors held equal – that behaviors tend to revert to the norm even if there is variability over time. While the norm itself may change over longer periods of time, groups will tend to revert to that new norm.

With your data “de-duped” and “rolled up” to unique individuals with a clean purchase history, you now need to break those groups up by the time since their first purchase (the age of the customer relationship) from the “normal” time (aka the norm) to repeat purchase.

You must segment the lowest to highest by age (recency) to target with ever more aggressive offers and communications. Once they missed your calculated IPT window, it’s time to get more aggressive.

Why? Those below the norm are the most likely to convert to repeat purchase, while those above the norm are less likely. We’ll also define the population of those most likely to convert as those who are less between the norm (average) and your calculated IPT.

How To: Solve Your One-Time Buyer Problem

Solving your one-time buyer problem is within your reach by following this simple 5-step process.

Step One: Assemble Key Data for One-Time Buyers

First, we’ll share and discuss the “Simple Six” One-Time Buyer Data Points you can use to solve your one-time buyer problem. The good news is that most organizations either have them readily available, or can put them together with some help.

- Valid customer record & contact information

You must have a deduplicated single record of the customer with all transactions rolled up under them in order to know who your one-time buyers are (and aren’t). You also need sufficient personally identifying information (PII) and a method of contacting them. This which includes their full name and a combination of postal/delivery address, phone, cell phone, and email. These are required to both complete a valid/merged customer record and provide a means to contact them with a personalized series of communications that are unique to their current state/situation and behavioral profile. - First Transaction Information, Buyer Source and Offer

You will need to know when that first transaction took place, what was purchased, if a special offer was tendered, and the source of the customer. The number of items and the SKU’s in that critical first “trial order” are generally good predictors of the probability of a second transaction. - Transaction Amount

The amount the buyer spent on the first order says more than the profitability (or lack thereof) on the first sale. It’s also indicative in many cases with the probability that they will order again in the future. - What The Buyer Purchased

In addition to knowing how many items were in the order basket, we also need to know what they bought – including the Category and SKU of the item. - Date and Time of Transaction

These are really two separate data points we split out and use for different purposes to solve the problem, but are usually captured in a single “time-date stamp” on the transaction. It tells us how much time has transpired since the first transaction so we can compare this buyer to all other buyers and determine whether or not they are more likely to buy again. Going beyond just “recency,” we can gauge one or more purchase windows for the individuals with a higher probability of a second transaction — or determine if they are just a lost opportunity. - The Profile or Buyer Persona

A deceptively simple question… who is your buyer? Demographics and lifestyle intelligence give us an extra advantage in understanding who our one-time buyers are. Are they affluent or of limited means? Do they have children at home? Are they skewed towards Millennials, Generation X, or Boomers? Merely using a well-worn story about your customer is an assumption or shortcut that has proven detrimental in cracking the one-time buyer problem. “Our customer is young, rich and beautiful” may be a true statement, but what about the 1x buyers who are Boomers? Will you be relevant or tone deaf? The answer to this question helps determine whether or not you will move a trial buyer into loyalty and an evergreen stream of profitability.These are very different customers, and our communications can be engineered in simple ways to spark them into a transaction and perform better when we speak in their voices and evidence our relevance to the customer. For example, personalizing an email’s subject line, hero shot, or the cellophane wrapper in a package can go a long way towards subsequent sales or more missed opportunities down the road.

Step Two: Rank Your One-Time Buyers by Aging

When we rank buyers by aging (a.k.a, recency), we’re determining how long it has been since they spent with us (note: this is not a ranking based on the age of the person). When we do this, we find out who has bought more recently and who hasn’t bought in a long time. This spectrum can be expressed as a distribution. In most data sets, you would expect to see a bell curve also called a normal distribution.

However, your frequency of purchases almost certainly does not follow a “normal” distribution. It most likely either has a huge spike around 1 purchase and then gradually falls to insignificance. Take a look at the example below. This visual is representative of the pattern we have observed across hundreds of brands when they first ingest their data into BuyerGenomics.

However, your frequency of purchases almost certainly does not follow a “normal” distribution. It most likely either has a huge spike around 1 purchase, or is negatively skewed.

A real example of distribution by purchase shows that one-time buyers skew well below the often imagined “norm” or center point in a normal distribution. This negative skewness illustrates that while it may seem “normal” that the typical customer buys a few times, we can clearly see in retail customer bases that most customers buy just one-time. This illustrates the need for addressing the problem proactively and early.

Notice also how the best spending customers that are the most loyal to the brand and have less time between their purchases, a requirement for a customer who spends a lot more. This is not to be confused with the fact that the majority of revenue is coming from the very large population of one-time buyers. Instead, it underscores the magnitude of the opportunity to sell again to your one-time buyers.

Step Three: Calculate the Cadence of Two-Time Buyer Purchases

Fortunately, we don’t have to solve the one-time buyer problem using only data about our one-time buyers. This is because all repeat buyers were once one-time buyers. Otherwise, it would be nearly impossible.

You almost certainly already have some two-time or more buyers. These individuals also have value in predicting when future purchases happen. The key is in the timing between the first and second purchase. Therefore, the goal is to understand both that behavior and its respective timing.

Step Four: Calculate The Inter-Order Purchase Time

We start identifying that window by looking at when historically our buyers made their second purchase. That’s measured as the difference between the date of the first purchase and the date of the second purchase in days. You’ll have to do this for every customer, next, compute the median number of days. We refer to this as the Golden Window for trial buyers.

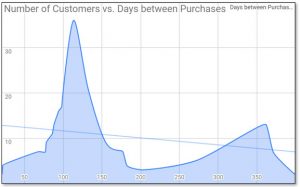

Lastly, if we were to look at the distribution of the number of days between first and second purchase, we could determine if our repeat buyers might fall into different groups or clusters of behaviors that warrant further segmentation.

In the example below we have a distribution of customers by the days between purchase. In this particular example, there is a high probability opportunity to sell at about 114 days, and a second (even if its smaller) opportunity to sell at around twelve months.

The one year window is sometimes referred to as an anniversary purchase, and may coincide with a birthday or seasonal event (like travel for spring break). These cases in which more than one opportunity exist may indicate a dual universe with different types of customers, suggesting assignment to different communication groups to take full advantage of different buying behaviors.

Step Five: Campaign Execution

When we’re entering one of the spikes on the distribution, we see the probability to make the sale has increased based on the timing. This is an opportunity to sell, and we need to contact the customer and make a compelling offer. The conversion rate can be improved by leveraging the other data points we described in the “Simple Six” earlier, including the following:

The initial source and offer that led the customer to her first purchase offers key insights on those offers and discounts that will work in the future.

The Transaction Amount tells us if they are a high ticket buyer and if we should position more premium products. This also requires us to consider the number of items in the first cart. Many low cost items vs. a single high ticket item are indicators of different types of buyers. Your offer should distinguish between them.

Your buyer’s demographic and psychographic profile is also an opportunity to tailor your creative and messaging around him/her. If we know our one-time buyer is a Millennial, Generation Z, or a “Global,” we’ll need to communicate differently than if they are a Boomer.

Tailoring subject line, creative, message, and offer/call-to-action in either an email or the cover of a catalog or postcard has been shown to increase both response and revenue per campaign.

Some Customers Are Already “Lost”

There is a portion of your one-time buyers that stopped buying from your brand (or at least from you) long ago relative to those who bought a second time. These individuals have the lowest probability of buying again, yet should be the target of “reactivation campaigns.”

By personalizing a reactivation offer based on what we know of this one-time buyer, it increases the likelihood of obtaining a second purchase. If the data shows that the customer has a high potential value, we would be foolish not to try and engage them. Systematic testing of reactivation offers by segments provides retailers with the best opportunity to increase purchases from one-time buyers.

Conclusions

By definition, one-time buyers are retailer’s largest customer retention opportunity. Increasing customer retention rates is one of the most significant opportunities that retailers have to improve profitability, according to many published studies. Thus, the one-time buyer problem is one worth solving.

This white paper has identified a simple 5-step process to addressing the one-time buyer opportunity. While most retailers offer a welcome series of communications, the opportunity exists for many retailers to improve upon such series by applying the simple data elements and promotion timing insights mentioned in this white paper.

For more information about how you can address your one-time buyer opportunity, contact the author, Mike Ferranti at mferranti@buyergenomics.com.